- Home

- John J. Gschwend

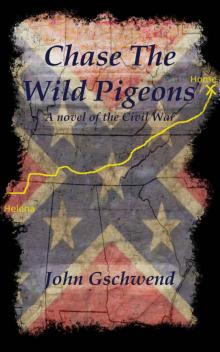

Chase The Wild Pigeons

Chase The Wild Pigeons Read online

CHASE THE WILD PIGEONS

John J. Gschwend Jr.

Chase The Wild Pigeons

All Rights Reserved © 2011 by John J. Gschwend Jr.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

http://civilwarnovel.com

dedicated to my family and the ones that persist and never give up

Note

The American Civil War was one of the most defining events in our country’s past. It changed the course of history so that we have become the greatest and freest nation on earth.

Slavery was also a large stain on our history. Many today can’t understand how such a merciless institution could have existed in this country. But it not only existed, it helped develop our country into what it is today.

African-Americans in bondage scraped out a life in the worst of conditions. They created a culture from the hardest of hardships. This is a history we must never forget, and we must know the true history of it. I could not imagine the life of waking up each morning knowing I belonged to another man, no matter how I was treated.

In this story I use dialect and words that are offensive to people today of all races. However, in 1863 this was everyday life, no matter if it was offensive or not. I researched extensively slave narratives, diaries, and letters. I desired to put the reader right there in that slice of time. Please know this was my only intention.

History is concrete; it only happened the way it happened. However, the record left behind may not always be the absolute truth. This novel was born from my research and my love of history. I sincerely hope my characters and my story live in the truth.

Best wishes,

John J. Gschwend Jr.

They Are No More

These species “live” in this story

American Chestnut

It has been estimated the American Chestnut tree once numbered over 3 billion. It was an important tree in the eastern forests of North America. It could reach over 150 feet tall and 10 feet in diameter, and it was prized for its tasty nuts and the rot-resistant wood. Twenty-five percent of all trees in the Appalachian Mountains were American Chestnut trees. In the early 1900s, a blight swept through the forests of the East, and now there are few large chestnut trees left there, mostly shoots and saplings that struggle before the blight finally extinguishes them. The great chestnut forest exists no more.

Carolina Parakeet

The Carolina Parakeet lived in the forests of Eastern United States. The beautiful bird was mostly green with a yellow head and orange cheeks. The noisy emerald flocks sometimes raided agricultural fruits and grains. This, along with man’s destruction of its native forests, may have been its undoing. It was considered extinct by the 1930s. These beautiful birds could once be seen in vast, colorful flocks, but now they are no more.

Passenger Pigeon

In the 1800s there are estimated to have been over 4 billion passenger pigeons—some say 5 billion. By these estimates, forty percent of all the birds at that time in North America were passenger pigeons, perhaps the most numerous bird to ever exist on earth. They were hunted relentlessly, and their habitat was destroyed for man’s use. There are locations all over Eastern America named for these birds: Pigeon Forge, Pigeon Roost, Little Pigeon River. People of that time would have never believed the bird would someday be absent from the sky. Many today don’t know they even existed. The last birds died in the early 1900s. Martha was the last passenger pigeon in captivity to die. She passed away at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. They once blackened the sky like dark clouds—now they are no more.

Chapter 1

Yankee-occupied Helena, Arkansas, May 1863

Darkness crawled across the overgrown graveyard. The headstones were bent and canted from neglect and shoved aside by determined bushes and saplings. A smoky fog had rolled in off the Mississippi River, floating through the cemetery like many ghosts.

Joe snuggled in behind a big headstone, knowing the Yankee sergeant would be coming soon; he had learned the soldier’s routine well. Joe looked over his shoulder; his partner was hidden behind a square, green-furred headstone. That’s right, Curtis; stay alert. We can’t afford to be caught, have to complete our mission for the cause.

Joe didn’t know why these Yankees had held up here in Helena instead of going on down to Vicksburg where the fighting was. It didn’t matter; they were here, and he was going to do his duty.

He settled in for the wait, had to have patience. He placed his face against the stone, cold and damp. He felt the inscription with his fingers. Curious, he backed off enough to read it. There barely was enough light, but he made out:

Allen Buford

Born 1802 Died 1851

May the angels guard him for eternity.

Joe felt a shiver, thought about looking for the angels.

“Psst!”

Joe started, then whirled. Curtis was pointing. Joe turned. The big Yankee was coming down the path. In the late gloom, his uniform appeared more black than blue. It was him, Sergeant Davis of Iowa.

Joe buried behind the headstone like a lizard under a shingle. Everything was automatic now. They had planned it well. They had practiced the escape. He was ready. He felt an electric screw in his chest and drumming in his ears, but he was ready.

The Yankee drifted down the dark, foggy path like a demon. He was a huge man, the biggest Yankee at Helena. He stopped at the exact place Joe had planned, slowly scanned the area, his Springfield rifle covering the area in a smooth circle, the bayonet on the end like a medieval spear.

Joe tried to melt into the back of the headstone. He knew Curtis was doing the same.

The Yankee finally seemed satisfied he was alone. He dropped a handful of leaves by a stump. There was a convenient chunk of firewood standing about eight inches beside it. The big man leaned his gun against a headstone, then unbuttoned his pants, and they fell to his ankles. He lowered his shining butt down on the stump and firewood—a homemade privy. Soon the music began—he was sputtering and spewing like a clogged flute.

Joe grinned. He had heard the soldiers call it the “Arkansas Quickstep.” They had all sorts of afflictions and diseases, living in cramped quarters and not being used to the southern climate.

Curtis giggled behind him.

Sergeant Davis snapped his head in that direction. “Who’s there?”

Joe turned toward Curtis, but his partner was hidden well. He’s going to get us shot, Joe thought. He was usually scared of his own shadow—now he’s laughing.

Davis turned back, must have assumed it was the wind. The sputtering began again.

Joe got to his knees. He was going to do this right. This mission would go off perfectly. He squeezed the weapon in his hands.

Davis grunted and his rear popped like a cork shot out of a bottle.

Curtis snickered.

Davis yelled, “Who the hell is over there? Answer me, damn it!” He reached for his musket.

Joe knew it was time. He leaped to his feet, jerked the rope in his hands. The rope snapped tight, catapulted leaves and sticks from the ground, then snatched the chunk of firewood from under Sergeant Davis’s right cheek. Davis’s arms fanned the air for purchase, but found none. His left cheek let go of the stump, and he landed butt-first into his own stink.

Curtis screamed laughter.

Joe struck out for the escape route. “Come on, Curtis!”

Davis tried to stand, slipped, and fell back into his mess. “Who the hell is over there?”

Joe stopped.

“No, Joe, keep going,” Cur

tis said. “We’ve been lucky so far, let’s don’t push it.”

Joe grinned. He turned toward the darkness that hid Davis and whistled “Dixie.”

Davis replied instantly: “Joseph Taylor! You little runt!”

Joe cut out for home with Davis’s yells fading behind him.

***

It was black dark when Joe ran up to the house. He snatched the backdoor open and flew in, his union kepi pulled down tight on his head, and his blonde hair dark with sweat. The kitchen, as always, smelled of sweet wood smoke. A brown hand grabbed his shoulder as he slammed the door. Joe turned to see Aunt Katie Bea glaring at him. She meant business. She always meant business.

“What you doing running in the street like that?” She let his shoulder go and crossed her arms—her business position. “I done told you over and over to stop running after dark. One of them Yankees gonna shoot you yet. You know they jumpy.”

“Pshaw, I ain’t worried about them Yankees.”

“You be worried when I tells your uncle.” She jerked the kepi off his head and shoved it into his chest. “A twelve-year-old boy ain’t got no business running in the street after dark.” She went to the stove and stirred in a steaming pot.

“Now Aunt Katie Bea, you know you ain’t going to tell Uncle Wilbur on me.” However, he knew well that she was subject to tell. He peeped into the pot. “Mmm, what ya cooking?”

“We is having stew.” She smiled—she could change expressions in a twinkling. “That nice Yankee colonel is in the parlor with your uncle right now. He gonna take supper with us this evening.”

Joe looked down the hall, then turned back to Katie Bea. She was short, only five feet. Joe was almost as tall as she was. Her hair was straighter and her skin was lighter than most Negroes Joe knew. He believed she was mostly white, probably a quadroon, but they were all the same to him.

Peter came through the backdoor with a load of firewood. He was Katie’s sixteen-year-old son. Even though he was a big boy, Joe believed he could take him if it ever came down to it. Joe could take most anyone.

“Peter, that’s enough firewood,” Katie Bea said. “Lawd, it too hot in here now. The kitchen should be outside the house like it supposed to be.” She mopped her brow with her apron. “You, go put the cow up after you stack that wood.” She straightened her apron and went into the hall leading to the parlor.

“Boy, I heard what you did,” Peter said as he stacked the firewood by the stove.

Joe grabbed a spoon and stole some stew. “What ya talking about?”

“You know what I’m talking about. Someone put a chicken snake in that private’s knapsack down at the river.”

“Weren’t me.”

“You and your friend Curtis.”

“I didn’t even see Curtis yesterday.”

Peter stood and smiled. “Who said anything about yesterday?”

Joe hated him when he outsmarted him like that—wise ass darky.

Katie Bea came back into the kitchen. “Boy, get outta that stew.” She shooed him away. “You two get ready for supper.”

“I need to tend the cow first,” Peter said and smiled at Joe before he went out the door.

Joe stuck his tongue out, and Katie Bea popped him with a rag.

“Boy, show some manners. I ain’t raising you to be no heathen. Now go tell the gentlemen supper will be set in just a few minutes. Get outta here and worry them a spell.”

Joe crept down the hall, stopping short of the parlor. The door was open and he could see the men, but the hall was dark and they couldn’t see him. Joe had often played as if the hall were his cave. He stopped to listen. He had learned that the only way for a twelve-year-old to learn anything was to spy, but it was important not to get caught. He had learned that the hard way—had he ever.

Colonel Frank Russell sat with his legs crossed at the end of the sofa, and Dr. Wilbur Taylor sat across from him in his favorite chair. Dr. Taylor smoked on his pipe as he usually did while in the parlor. That pipe smelled sweet. Joe would smoke one when he got the chance. He would try it now, but he knew Dr. Taylor was wise to that because he never left it where Joe could sneak it.

Joe glanced back down the long hall—it was safe. Katie Bea couldn’t see him, so he settled in to listen.

“For the life of me, I can’t begin to understand why you would leave Pennsylvania for this God-forsaken place,” Colonel Russell said.

“I didn’t anticipate there would be a war, that’s for sure,” Dr. Taylor said, poking in his pipe. “I just wanted a change, and this fast-growing, frontier town fit the bill, and it’s on the river so I’m still close to civilization.”

“There are plenty of small towns up North,” Colonel Russell said, dragging a large cigar from his shirt pocket. Dr. Taylor lit it for him.

“I can’t put a reason that I chose the South. It is all America—was America.”

“It is still all one America. We will make sure of that.”

“I do pray it all turns out for the best. You see, Colonel, I have a brother that took a bride from Mississippi and moved there and another brother that moved to Virginia, Joseph’s father. I guess that is strange to you.”

“Very strange indeed, Doctor. The first chance I get I’m going back North.”

“I like Southerners—they are a charming people, chivalrous and kind.”

The colonel exhaled and talked through the smoke: “Charming, chivalrous and kind? Are we talking about the same race that we’ve been fighting? Hell, slavery alone nullifies all that.”

“Most have nothing to do with slavery.”

“They sure are suffering a terrible war to keep the merciless institution.”

“You are more aware than I that there is more to this war than the institution of slavery.”

Colonel Russell waved a dismissal. “I know, Doctor. I sure didn’t come here to start a war with you. I know you are a transplanted Yankee and are good to the Negroes. Hell, you treat your slaves like family.”

Dr. Taylor stood. “Sir, Katie Bea and Peter are not slaves!”

Russell slowly rose. “Dr. Taylor, please, I do apologize. I’ve offended you, and here you have so graciously invited me to dine with you. Please let us sit.” He sat back down.

Dr. Taylor smiled weakly and eased into his chair.

“I just thought since they lived in the house with you and the boy that they were your servants.” He blew smoke. “You and Katie Bea are not—”

Dr. Taylor shot up from the chair again. “Colonel, you overstep you bounds, Sir!”

Joe had never seen his uncle so riled. Maybe a fight was brewing. If Uncle Wilbur had trouble, Joe would hit the colonel low—that was always his best strategy.

Colonel Russell stood. “Doctor, you are absolutely correct, and I do apologize again.” He bowed his head, and smiled. “And I’m damned if you don’t sound like a Southerner.”

Joe saw his uncle relax as the men sat.

“Well, Colonel, I reckon I see how you could have made the mistake. You are a guest in my home, and I should apologize to you also.”

Colonel Russell nodded and puffed on the stinking cigar.

“Katie Bea’s husband was a good friend, and when he died, I took them in,” Dr. Taylor said.

“He must have been a very dear friend for you to feel that indebted.”

“I could never repay the debt that I owed him, but Katie Bea and Peter are family to me now—not a debt to be repaid.”

This was getting too boring for Joe, so he pulled the kepi down tight and marched into the parlor. He saluted. “Hi, Colonel.”

“Joseph, pull that cap off in the house,” Dr. Taylor said.

Joe slid it off.

The cigar smoke was heavy and not at all as pleasant as the pipe smoke.

“What have you been up to, you little Rebel-Yankee?” Colonel Russell said, smiling.

Before he could answer, Dr. Taylor cut in. “If he and his troop keep getting into mischief, I will take a belt t

o the captain while the private watches.”

The colonel laughed, asked, “You and your troop wouldn’t know anything about a snake in Private Funk’s knapsack, would you?”

Joe realized with all the choking cigar smoke and the interrogations that this was not a good place to be.

“Aunt Katie Bea said supper would be ready in a few minutes.” With that statement, he slipped back toward the kitchen.

He was at the washbasin in the kitchen when someone knocked on the door. Katie Bea went to answer, but before she made it to the door, it became a pounding. She opened the door. It was jerked from her hand.

It was Sergeant Davis. “Where is that damn boy?”

Joe slipped unnoticed into the dark hall.

“Don’t you be a-coming in this house talking to me in that fashion,” Katie Bea said.

“You listen to me, darky. That little devil has messed with me for the last time, and an ass-whooping is what he will get.”

Dr. Taylor charged past Joe and into the kitchen. “Sergeant, what is the meaning of this intrusion?”

“I mean to give that boy a licking. You folks don’t seem to be able to handle him.”

“You get out of my home this instant!”

At that moment Peter came through the door. “What is that smell?”

“What does it smell like, boy? It’s shit.”

There were a couple more soldiers outside; they laughed.

Davis grabbed Peter by the shirt, snatched him inside, and slammed the door.

Joe was formulating a plan when Colonel Russell moved past him in the hall.

“Davis!” Colonel Russell barked when he entered the kitchen.

“Sir!” Davis shot to attention.

“What are you doing?”

“Colonel, it’s the boy again. He has gone too—”

Chase The Wild Pigeons

Chase The Wild Pigeons